Random Icons -

The making of

Personal Exhibition of EPVS

Curator: Anatole Pierre Fuksas

Spazio Bloomsbury Via della Pilotta 16 - 00187 Rome

Vernissage:

27 February 2009, 19.00

Opening time:

2-6 March 2009 10.00-13.30 / 14.00- 18.00

Video della mostra:

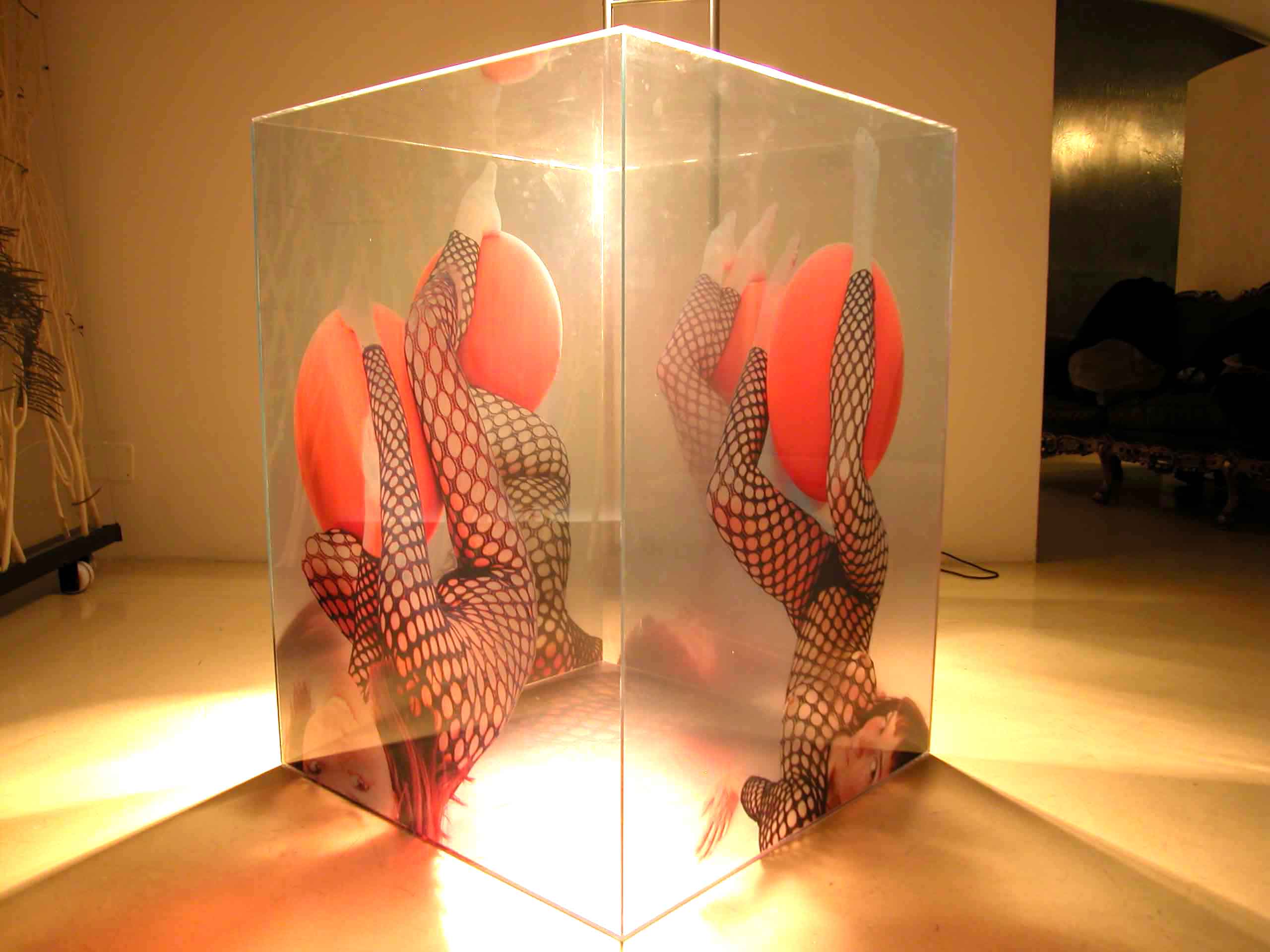

Dolls and Puppets

The making of an Icon might be explained in relativistic, chronotopical terms as a subtraction of space and time in which a person is previously immersed. In such terms, puppets and dolls have to be assumed as atemporal and atopic entities, disguisable in any possible fashion, since they do not belong to any specific here and now. Accordingly, the same dolls may be shown on stage as timeless princesses or nurses or whoever; just as placeless puppets might be sitting on dinosaurs, on a train or wherever. Defined Icons, therefore, are not limited to chronologically or locative specific roles or behavior. They fit any context: your next TV show, an advertisement from the fifties, the seat next to yours on the subway, a horse riding in the

The Ecology of Icons

As myths are deeply rooted in history, Icons were once people, more or less

popular gals, ladies, cool guys or random blokes. That’

Actions and Gestures

Accordingly, Icons perform gestures not actions. Indeed, the ecology of Icons is not defined by an Icon’s purposeful interaction with its own very narrow and deserted environment. Icons eventually move, but is that dancing? Icons eventually prowl sinuously, but is that seducing? Icons eventually move between balloons but why? Icons bump balloons on the floor; still, to what purpose? Icons are actually living somewhere on this planet, but they are confined to a locatively meaningless nowhere, places that may be anywhere on Google maps or, more likely, on the ‘Map of the Strange’. Just as in time, Icons are eventually now, or tomorrow, let’s say yesterday, but who cares? They don’t.

The Artist as an Icon

It is common sense that artists love to be famous and recognized everywhere, as they are eager to outlive their human experience as people. That’s why they might be very concerned by processes of self-iconization. Common sense is wrong, however, at least when it comes to real artists. Indeed, they are more likely to aim at joining their Icons in the very same prisons to which they themselves confined them. That’s what a self-portrait tries to be: an artist’s desperate, tentative attempt to feel the same way his own victims feel after he ‘treated’ them, ‘worked them out’, in short iconized them. Indeed, in order to iconize his victims in the most effective way, the artist has to experience first-hand how it feels to be deprived of opportunities for action that once defined the extent of the nostalgically neglected belonging to mankind.

Anatole Pierre Fuksas